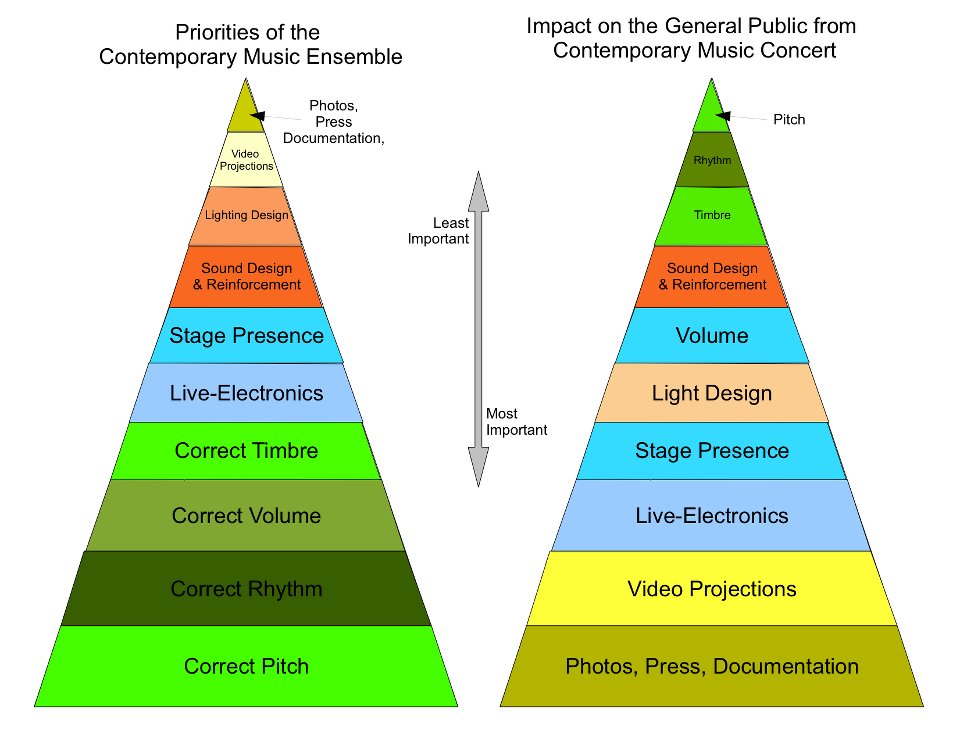

This graphic has been going around Facebook lately:

It is, of course, a huge oversimplification. In particular, correct pitch and rhythm are much more important than the graphic suggests. Sure, if a group plays a bunch of wrong pitches and rhythms, very few people in the audience will have any idea; if it’s a premiere, maybe only the performers and composer will know. But that actually makes it more important to get the pitches and rhythms right, not less — because if you get them wrong, the audience will just think they’re listening to a worse piece than they really are, and that can be pretty damaging in an era when so many people are prepared to dislike new pieces.

But there is some truth to the graphic as well. I’ve been to an awful lot of new music concerts where little to no attention was paid to the visual and dramatic elements of the performance — staging, lighting, and so on. (Video might be the most lazily handled element of all; much of what I’ve seen has been indistinguishable from a screensaver.) And maybe that doesn’t matter if you’re presenting highly cerebral music for an audience of specialists in a university composition department — but if you’re interested in drawing in non-composers, or even composers like me who are more interested in theater than theory, presentation is essential.

I’ve said all this before, several times on this blog and several million times in real life. But this time my purpose is not to complain about the troubles of the new music world; I want to talk about something I saw recently that was done right.

Last week, the Spektral Quartet put on a multimedia show called “Theatre of War.” It included films, poetry and a short play, as well as two musical performances. At the beginning, the group asked everyone to hold their applause until the end of the show. In between works the stage was dark, and the title of the next work was projected on a large screen, in silence. The lighting was theatrical — often just a single spotlight on whoever was on stage. One of the musical performances was the quartet doing George Crumb’s Black Angels; I have mixed feelings about that, not because of their performance, which was great, but because of the piece itself, certain sections of which strike me as unintentionally comical rather than somber or frightening. But I want to talk about the other one, Stress Position by Drew Baker.

Before the piece, all that appeared on the screen was the words “Stress Position,” with no explanation. Then Lisa Kaplan came out, sat down at a piano illuminated by a spotlight, and started hammering out an incessant minimal rhythm at the extreme ends of the instrument’s range, her left hand all the way at the bottom and her right hand all the way at the top. It took about a minute before I realized what was going on: the way that the piece forced her to keep her arms extended and her muscles tensed was an abstraction of the torture technique used by the US military at Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay during the Bush administration. Realizing this was sickening and terrifying. And here’s the thing: it wouldn’t have been sickening and terrifying if I hadn’t been allowed to discover it for myself. What made the piece so powerful was the fact that its symbolism was presented worldlessly, allowing the viewer to grasp its significance viscerally rather than analytically.

Afterward, I congratulated Drew Baker on not having written a program note, and it turned out he actually had written one — I just hadn’t noticed it in the program. Oops. Still, having the lights down the whole time meant that I couldn’t read the program note while the piece was being performed.

Coming back to “Theatre of War” as a whole, I also have to say that I found it very gratifying to see new music presented as part of a wider artistic and cultural landscape. So often the rest of the art world ignores scored music in favor of bands, and so often composers and new music ensembles isolate themselves from the rest of the art world. I think something like this is Good For Art. What I’m wondering now is: would an event like this, presenting new music alongside other contemporary art, work as well if the music were totally non-representational?

One Comment

(Just to clarify: I don’t have anything against the performance of highly cerebral music for an audience of specialists in a university composition department. But there’s already a ton of that going on, and it’s not what I’m interested in doing these days.)